Death of a Mere

.

The River Nene was once an important waterway, linking the lands to the west of the Fens with London and other ports. Goods included building stone (“Barnack Rag”), from the quarries near Stamford, wool, reeds, and later bricks. As it passed through the fens, it curved around areas of higher ground where there were settlements. “Holme” is an old Norse term for an island, and other local places with names ending in “-sey” were likewise raised, habitable land.

.

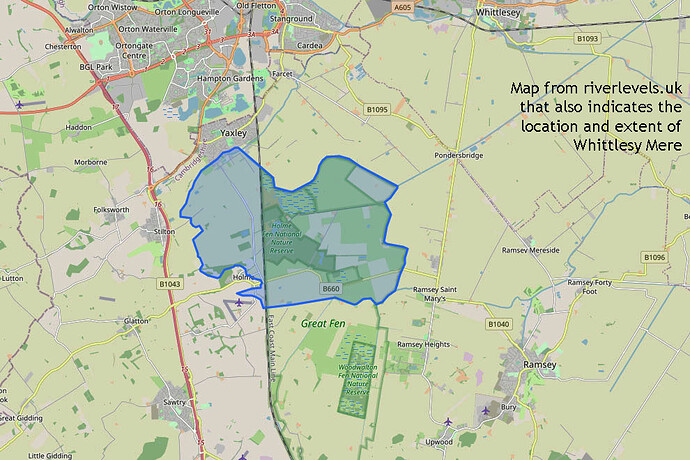

But the boats plying this trade had to tackle Whittlesey Mere, a natural lake along the way, and the largest of several lakes in the vicinity. This was difficult territory: the mere changed size (and depth) dramatically over the seasons, during the winter it would grow to perhaps 3 miles wide, and six miles long. The surrounding ground was dangerously soft: in February 1851, a young lad sank up to his armpits, remaining stuck for 19 hours, hidden by the reeds, until a passing labourer discovered him. In most places, the depth was minimal, and Fen Lighters (the traditional boats employed) had a very shallow draughts - effectively larger versions of the punts used by locals.

.

Pleasure trips on the mere became popular. “We came in sight of a great water, looked like some sea it being so high… It was 3 miles broad and six long. In the midst there is a little island where a great store of wildfowl breeds… it looks formidable and its often very dangerous by reason of sudden winds that rise like Hurricanes, but at other times people boat it round the Mere with pleasure, there is abundance of good fish in it.” (Celia Fiennes, 1697). By this time, the name of both mere and settlement had arrived at a consensus: the railway company demurred, and to this day the little station remains “Whittlesea”.

.

The Victorian enthusiasm for collecting wild plants and insects also had a big impact. Local people made money by sending trunks full of desirable specimens to London collectors, via the new railway, from Holme station. The trade, already threatened by over-collecting, died off after the drainage of the Mere, due to habitat change.

.

The Abbeys at Ramsey, Sawtry and Peterborough had all long held fishing rights on the mere. These were divided into ‘boatgates’ (one boat, three men, and specific size of net): the sale of licences for these brought in considerable income. In addition, Ramsey Abbey appears to have held the rights to levy a toll on shipping, helping to make it one of the richest. One local waterway (Monks Lode) was probably built by Sawtry Abbey to bypass the mere, and evade this tax.

.

So, when the drainage of the fens began in earnest in the 17th century, it was natural that Whittlesey Mere was a prime target. By this time, it was badly silted up, and slightly higher than the surrounding fens, following earlier drainage work. (The aptly-named Ramsey Heights is now a dizzying 2m above sea level: the Holme Fen posts, a few km to the west, are around 2m below it.)

.

The locals were mostly opposed to the draining, as it would deprive them of their traditional livelihood - wildfowling, fishing and reed cutting. Life might be hard, but it gave them a sense of belonging and community. The “Fen Tigers” sabotaged the dykes and sluices, and set reedbeds on fire. But, in time, the River Nene was re-routed, new drains built, and the change “from punt to plough” was largely complete. A tiny remnant of Whittlesey Mere (no more than 25m diameter) remains at Holme Fen – but you have to be shown where it is!

.

After the land was drained, the peat started to dry and contract so that the shrinkage increased - leaving the rivers and dykes at a higher level. In Railway Wood, some of the trees seem to stand on tiptoe – the ground has shrunk from around their roots. It became necessary to mechanically raise the water from the field ditches up into them. There were nine windmills in Woodwalton parish alone: later, these were replaced by steam, then diesel or electric pumps.

.

in 1851 William Wells (now the landowner, a gift from the crown for his his backing the drainage project) had an oak pile driven through the peat into the underlying clay beside Engine Drain at Holme Fen; he then cut the top to ground level, to monitor the peat subsidence. A few years later, the oak post was replaced by a cast iron column, with its top at the same level as the original post. As it was progressively exposed it became unstable, so steel guys were added in 1957, when a second iron post was also installed 6m to the northeast (claimed to have come from the Crystal Palace rubble: the original post was sunk the in the year of the Great Exhibition). The Homle Fen Posts now stand 4m above the ground.

.

The drained mere was never fully “tamed”. Some of it never became stable enough for agriculture, and it was allowed to scrub over. Today, Holme Fen is probably both the lowest point of mainland Britain, and also the largest lowland Birch wood. A branch railway ran along the edge of it, linking Ramsey and places further east to what is now the East Coast Main Line. Despite ever more loads of ballast, the track remained unstable, and restricted by very low speed limits. Stand near the northern Holme crossing (“Queenie’s” - named after one of the last keepers), and you can feel the earth shake quite dramtically as a train passes on the ECML. Lock your car, and the tremors will likely set off the alarm.

.

Powte’s Complaint: (Anon, c. 1850. A ‘powte’ is a lamprey.)

Come, Brethren of the water, and let us all assemble,

To treat upon this matter, which makes us quake and tremble;

For we shall rue it, if’t be true, that Fens be undertaken

And where we feed in Fen and Reed, they’ll feed both Beef and Bacon.

.

They’ll sow both beans and oats, where never man yet thought it,

Where men did row in boats, ere undertakers brought it:

But, Ceres, thou, behold us now, let wild oats be their venture,

Oh let the frogs and miry bogs destroy where they do enter.

.

Behold the great design, which they do now determine,

Will make our bodies pine, a prey to crows and vermine:

For they do mean all Fens to drain, and waters overmaster,

All will be dry, and we must die, 'cause Essex calves want pasture.

.

Away with boats and rudder, farewell both boots and skatches,

No need of one nor th’other, men now make better matches;

Stilt-makers all and tanners, shall complain of this disaster,

For they will make each muddy lake for Essex calves a pasture.

.

The feather’d fowls have wings, to fly to other nations;

But we have no such things, to help our transportations;

We must give place (oh grievous case) to horned beasts and cattle,

Except that we can all agree to drive them out by battle.